Glauber sobre Fuller

E algumas precisões sobre Guy El Tsotsie, por Dmitry Martov

O curso “O Western: formas e convenções” acabou nos dias 20 e 22 deste mês; quem ainda quiser se inscrever para ter acesso completo ao material do curso e às aulas online gravadas pode clicar nos links acima.

Deixarei para a próxima postagem alguns comentários sobre as aulas e a participação dos que se inscreveram no curso (e que foram mais interlocutores do que alunos ao longo das aulas). Essa postagem será a última que publicarei aqui relacionada ao conteúdo do curso.

No meio-tempo entre esta e a próxima postagem, estarei respondendo alguns e-mails que ficaram pendentes.

Mas antes de seguir com o material anunciado no título desta postagem, gostaria de agradecer enormemente a todos os que participaram do curso pelo tempo, pelo entusiasmo, pela participação e pelo interesse.

--------------------

Na segunda aula da turma em língua inglesa, o Saket Edidi perguntou se eu sabia da existência de algum texto do Glauber sobre o Fuller. Respondi que não sabia se havia algum texto sobre Fuller escrito pelo Glauber; o Gustavo Salvalaggio em seguida disse que havia sim um texto do Glauber numa coletânea, “Crítica Esparsa (1957-1965)”, cujo PDF ele me passou. Fiquei de postar por aqui mesmo o original e a tradução em inglês, mas não tive tempo de fazê-lo durante o curso.

O texto:

DRAGÕES DA VIOLÊNCIA

(Forty Guns, 1957) Produção, argumento e direção: Samuel Fuller – No preto e no branco, contra a sofisticação colorida do cinemascope, Samuel Fuller nos oferece a segunda obra-prima de western do ano: Dragões da violência, filme que rompe quase completamente com a linguagem tradicional e já cansativa do gênero.

A primeira obra-prima de western desse ano foi Sem lei e sem alma [Gunfight at the O.K. Corral], de John Sturges, onde também já existia essa deliberação de abandonar certos caracteres em busca de nova expressão. A balada cantada no início, o duelo na rua, a partida do herói no final, embora permanecessem em Sem lei e sem alma, já eram utilizadas em sentido menos convencional. Não era a procura de efeitos chocantes, como ocorria (e ainda ocorre) com direitos menos talentosos. Agora, em Dragões da violência, embora tais elementos estejam presentes, o sentido em que são utilizados já é outro ainda mais distante. E a sua vantagem sobre Sem lei e sem alma reside em criações do diretor Samuel Fuller: verdadeiros achados de linguagem cinematográfica que acrescentam à sétima arte valiosa contribuição.

*

Já a sequência de início, é excelente: o herói vem calmamente por uma estrada empoeirada em companhia de seus dois irmãos. Não há música. A cena é tomada do alto em plano geral. Súbito, uma sombra invade o quadro gradativamente e um rumor abafado de tropel de cavalos se faz ouvir. Há um corte sobre pés de cavalos correndo, saltando o som dos cascos em corrida para primeiro plano. Corta para o herói e seus irmãos atentos, para o som. Volta-se novamente aos pés do cavalo, e assim a sequência prossegue nesse mesmo ponto, até que os quarenta cavaleiros correndo atrás da bandoleira Jessica (mulher vestida de preto em um cavalo branco), cruzam com a charrete do herói, assustando os cavalos atrelados e lançando-lhes poeira na cara.

Outra sequência que revela o talento sempre crescente de Samuel Fuller é o encontro do herói com o garotão desordeiro, bêbado e armado na rua da cidade. Todos esperam o comum duelo. O herói marcha calças pretas, toalha de banho no pescoço (interrompera o banho para ir acabar a desordem), enquanto o bandido o espera de arma em punho. O tiroteio é iminente. A câmera corta sobre os pés do herói avançando alternado com o bandido, que vai ficando medroso quando reconhece o famoso atirador. Nesse jogo de planos que vai criando a tensão dramática, há um corte inesperado para os olhos do herói em grande primeiro plano e depois outro para primeiro plano da mão do bandido. Esses planos se sucedem até que novo corte surge: a câmera, de pouca distância, avança rapidamente sobre a mão do bandido, que fica dura e solta a arma: esse avanço de câmera traduz a força do olhar do herói sobre o bandido fraco de personalidade ante o xerife de fama e coragem. O olho do herói aproxima-se da mão do bandido. Desta forma, o cinema expressa através das imagens puras. E isto é que é verdadeira linguagem cinematográfica.

Dragões da violência ainda é pontilhado de outras sequências fabulosamente bem armadas. Muitas surpreendentes, que não devem ser comentadas, a fim de não tirar do público ou mesmo do espectador mais atento o prazer do inesperado. E o inesperado em Forty Guns não é truque fácil. Nem brincadeira, à maneira de Hitchcock. É cinema sério.

O senão, mesmo o defeito desse filme de Samuel Fuller, reside no final: a concessão ao público é feita, quando poderia ser suprimida. Barry Sullivan e Gene Barry compõem ótimos tipos. Barbara Stanwyck, muito velha, está em ruínas.

(Jornal da Bahia, Salvador, 8 de outubro de 1958, 2º Caderno, coluna “Jornal de Cinema”, p. 3)

Algumas horas depois da terceira aula, recebo este e-mail do Dmitry Martov:

Olá Bruno,

ótima aula hoje, como sempre.

Estou enviando algo que postei no Facebook, talvez você ache interessante (ou talvez seja conhecimento comum? Mas não consegui encontrar nenhuma informação sobre isso online):

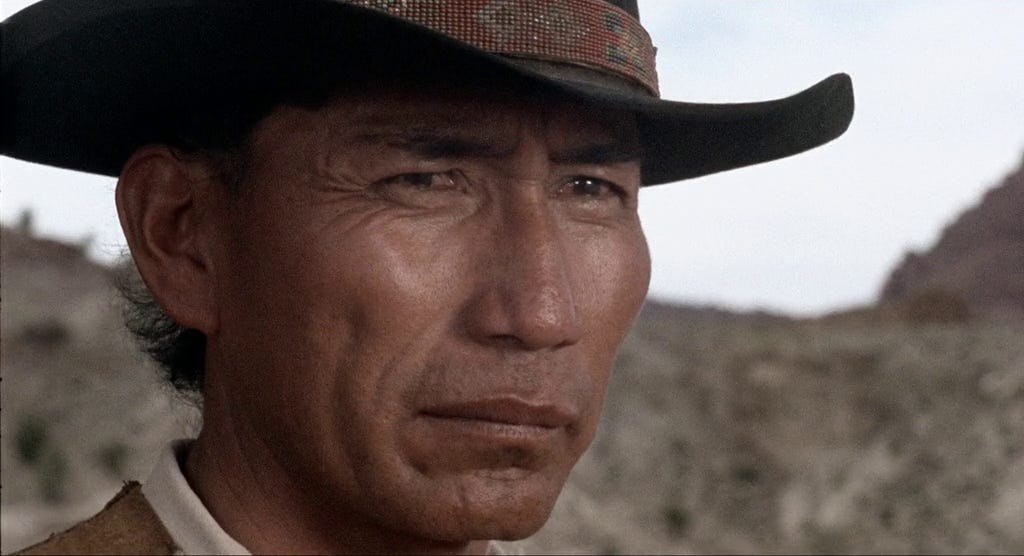

“No comentário em áudio do Blu-ray de The Shooting (1966), ocorre uma troca intrigante entre o diretor Monte Hellman, Bill Krohn e Blake Lucas:

- ‘Este sujeito aqui, nós o escalamos na reserva Navajo, e eu não fazia ideia de que ele era um astro de cinema famoso.’

- ‘Ah, é? Qual o nome dele?’

- ‘Guy El Tsotsie. E quando o filme estreou na França — antes de qualquer outro lugar — eles já o conheciam de um filme anterior. Assim que ele apareceu na tela, o reconheceram pelo nome.’

O que é curioso, porque no IMDb, The Shooting continua sendo o único crédito de atuação de Guy El Tsotsie. Dificilmente o currículo de um homem cuja entrada em cena faria os cinéfilos franceses se cutucarem uns aos outros no escuro.

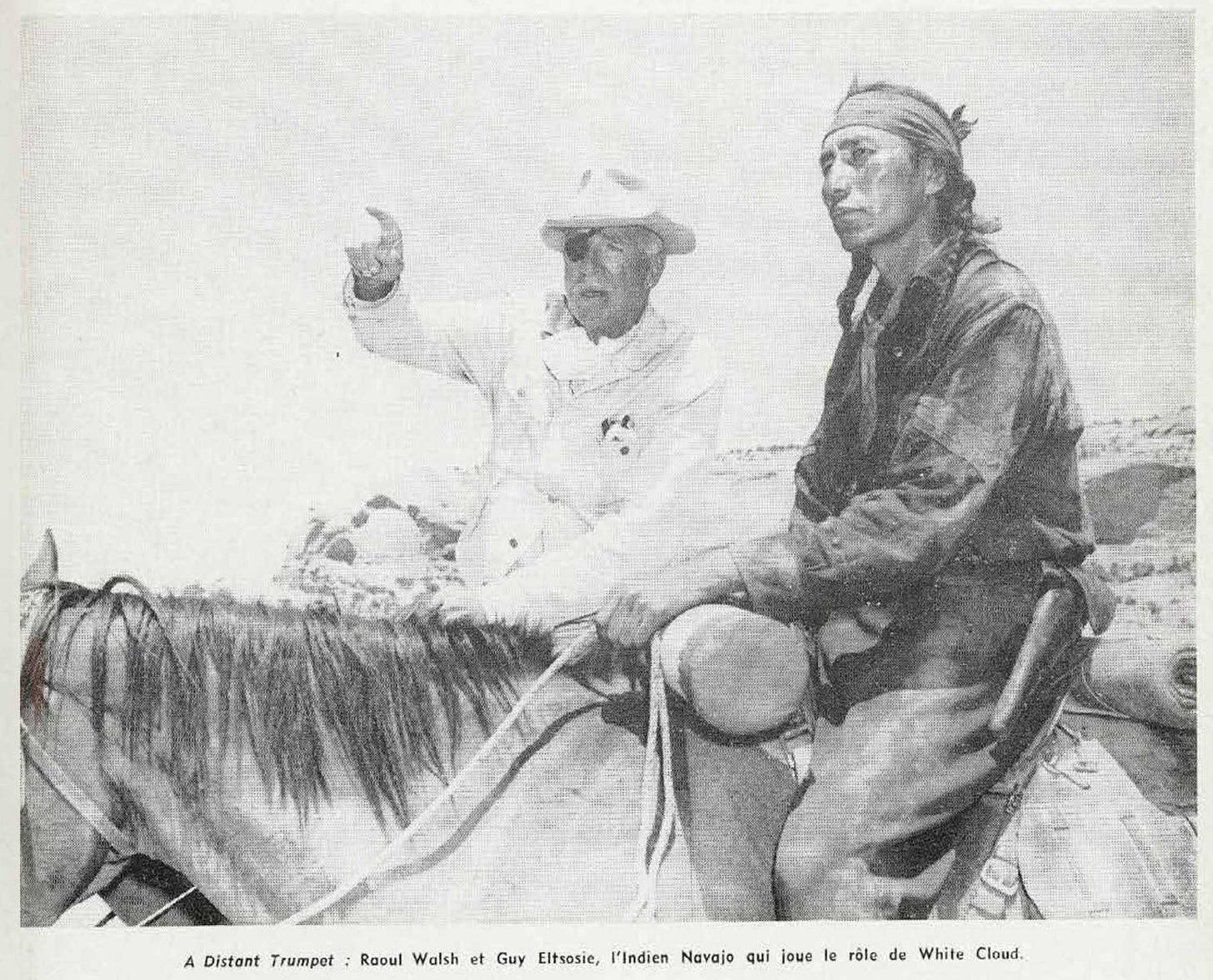

As coisas ficam ainda mais interessantes quando se nota que o IMDb também lista um ator chamado “Guy Eltsosis” (sic) como um soldado não creditado em A Distant Trumpet (1964), de Raoul Walsh. A principal personagem nativo americana do filme — o ex-chefe que se tornou batedor, White Cloud — também não é creditada e é incorretamente atribuída online a John War Eagle. Na verdade, o papel de White Cloud foi interpretado por Guy Eltsosie, um navajo de 37 anos de Cedar Ridge, Arizona — o mesmo homem que reaparece mais tarde no filme de Hellman.

Mesmo que o público francês em 1968-69 (quando The Shooting foi exibido pela primeira vez na França) não o reconhecesse diretamente do filme de Walsh, eles poderiam muito bem conhecer seu rosto e até mesmo seu nome pelo Cahiers du cinéma, edição dupla nº 150-151 (dezembro de 1963-janeiro de 1964). O artigo de Jean-Louis Comolli, “Amérique à découvert”, inclui uma fotografia de Walsh com Eltsosie, canonizando-o assim como uma “estrela de cinema famosa” anos antes de The Shooting chegar às telas europeias.

#uselessfilmstudies

Atenciosamente,

Dmitry

In the second class of the English language course, Saket Edidi asked if I knew of any texts by Glauber about Fuller. I replied that I didn’t know if there were any texts about Fuller written by Glauber; Gustavo Salvalaggio then said that there was indeed a text by Glauber in a collection named “Crítica Esparsa (1957-1965)”, the PDF of which he sent me. I planned to post both the original and the English translation here, but I didn’t have time to do so during the course.

The translation:

FORTY GUNS

Production, screenplay, and direction: Samuel Fuller – In black and white, in contrast to the colorful sophistication of CinemaScope, Samuel Fuller offers us the second Western masterpiece of the year: Forty Guns, a film that breaks almost completely with the traditional and already tiresome language of the genre.

The first Western masterpiece of the year was John Sturges’ Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, which also deliberately abandoned certain elements in search of new expression. The ballad sung at the beginning, the street duel, the hero’s departure at the end, although present in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, were already used in a less conventional way. It was not a search for shocking effects, as was (and still is) the case with less talented filmmakers. Now, in Forty Guns, although such elements are present, the way they are used is even more distant. And its advantage over Gunfight at the O.K. Corral lies in the creations of director Samuel Fuller: true discoveries of cinematic language that add a valuable contribution to the seventh art.

*

The opening sequence is excellent: the hero calmly rides down a dusty road accompanied by his two brothers. There is no music. The scene is shot from above in a wide shot. Suddenly, a shadow gradually invades the frame and a muffled sound of horses galloping can be heard. There is a cut to the feet of horses running, with the sound of hooves galloping in the foreground. Cut to the hero and his brothers, alert to the sound. The camera returns to the horses’ hooves, and the sequence continues in this same vein until the forty horsemen accompanying the bandit Jessica (a woman dressed in black on a white horse) cross paths with the hero’s carriage, startling the harnessed horses and throwing dust in their faces.

Another sequence that reveals Samuel Fuller’s ever-growing talent is the hero’s encounter with the rowdy, drunk, armed young man on the city street. Everyone expects the usual duel. The hero wears black pants and a bath towel around his neck (he interrupted his bath to go and settle the dispute), while the bandit waits for him with his gun drawn. The shooting is imminent. The camera cuts to the hero’s feet as he advances, alternating with the bandit, who becomes fearful when he recognizes the famous shooter. In this interplay of shots that creates dramatic tension, there is an unexpected cut to the hero’s eyes in close-up and then another to a close-up of the bandit’s hand. These shots follow one another until a new cut appears: the camera, from a short distance, quickly advances on the bandit’s hand, which stiffens and drops the gun: this camera movement conveys the power of the hero’s gaze upon the weak-willed bandit in the face of the famous and courageous sheriff. The hero’s eye approaches the bandit’s hand. In this way, cinema expresses itself through pure images. And this is what true cinematic language is.

Forty Guns is also punctuated by other fabulously well-crafted sequences. Many surprising, which should not be commented on, so as not to deprive the audience, or even the most attentive viewer, of the pleasure of the unexpected. And the unexpected in Forty Guns is not an easy trick. Nor a game, in the manner of Hitchcock. It’s serious cinema.

The drawback, even the flaw in this Samuel Fuller film, lies in the ending: the concession to the audience is made when it could have been suppressed. Barry Sullivan and Gene Barry make up excellent characters. Barbara Stanwyck, very old, is in ruins.

(Jornal da Bahia, Salvador, October 8, 1958, 2nd Section, “Jornal de Cinema” column, p. 3)

A few hours after the third class, I received this email from Dmitry Martov:

Hey Bruno,

great class today, as always.

Here is something I posted on Facebook, you might find this interesting (or maybe this is common knowledge? but I couldn’t find any info about this online):

“In the Blu-ray audio commentary for THE SHOOTING (1966), an intriguing exchange unfolds between director Monte Hellman, Bill Krohn, and Blake Lucas:

— “Now this character here we cast from the Navajo reservation, and I had no idea he was a famous movie star.”

— “Oh yes? What’s his name?”

— “Guy El Tsotsie. And when the picture opened in France — before anywhere else — they already knew him there from a previous film. As soon as he appeared on screen, they recognized him by name.”

Which is curious, because on IMDb THE SHOOTING remains the only acting credit for Guy El Tsotsie. Hardly the résumé of a man whose entrance would cause French cinephiles to nudge each other knowingly in the dark.

Things get more interesting when you notice that IMDb also lists an actor called “Guy Eltsosis” (sic) as an uncredited trooper in Raoul Walsh’s A DISTANT TRUMPET (1964). The film’s main Native American character — the former chief turned scout, White Cloud — is likewise uncredited and incorrectly attributed online to John War Eagle. In fact, the role of White Cloud was played by Guy Eltsosie, a 37-year-old Navajo from Cedar Ridge, Arizona — the same man who later reappears in the Hellman film.

Even if French audiences in 1968–69 (when THE SHOOTING was first screened in France) didn’t recognize him from Walsh’s film directly, they might well have known his face and even his name from Cahiers du cinéma, double issue nos. 150–151 (December 1963–January 1964). Jean-Louis Comolli’s article “Amérique à découvert” includes a photograph of Walsh with Eltsosie, thus canonizing him as a “famous movie star” years before THE SHOOTING ever reached European screens.

#uselessfilmstudies

Best,

Dmitry